Perplexing Presentations (PP) / Fabricated and Induced Illness (FII) in Children Practice Guidance

Perplexing Presentations (PP) / Fabricated and Induced Illness (FII) in Children Practice Guidance

This practice guidance is produced jointly with the City of York Safeguarding Children Partnership.

Introduction

Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII), by parents or carers, is child abuse and can cause significant harm to children. FII involves a well-child being presented by a parent/carer as ill, or a disabled child being presented with more significant problems than he/she has. This may result in extensive, unnecessary medical procedures and investigations being carried out to establish the underlying causes for the reported signs and symptoms. These interventions can result in children spending long periods of time in hospital, and some, by their nature, may also place the child at risk of suffering from harm (physical illness, disability or even death). FII can lead to emotional difficulties for the child and confusion over their own health status. Professionals must focus on the impact of FII on the child’s health and development – this is crucial to ensure an appropriate safeguarding response.

The definition of FII has been extended by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) Child Protection Companion (2013), to include the term ‘Perplexing Presentations’ (PP). In February 2021, the RCPCH introduced new guidance for paediatricians on the management of Perplexing Presentations (PP), Fabricated and/or Induced Illness (FII) in Children. https://childprotection.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/perplexing-presentations-and-fii/

It is recognised that there is often uncertainty about the criteria for suspecting or confirming PP/FII and the threshold at which safeguarding procedures should be initiated. In the UK, there has been a shift towards earlier recognition of possible FII, (which may not amount to likely or actual significant harm), and subsequent intervention. The RCPCH guidance recommends that a new collaborative approach is needed in situations where the presentation is’ perplexing’. This process aims to ensure:

- Children receive appropriate health care for their needs

- An improvement in children’s health and well-being

- Whenever possible, working collaboratively with parents

Aim of this Guidance

This guidance aims to support professionals from all agencies to recognise and respond to possible PP/ FII to effectively safeguard and achieve better outcomes for children. It is necessarily detailed as it reflects the often highly complex nature of this form of abuse. It is also acknowledged that there are challenges for all professionals in terms of recognising and responding to possible PP/FII.

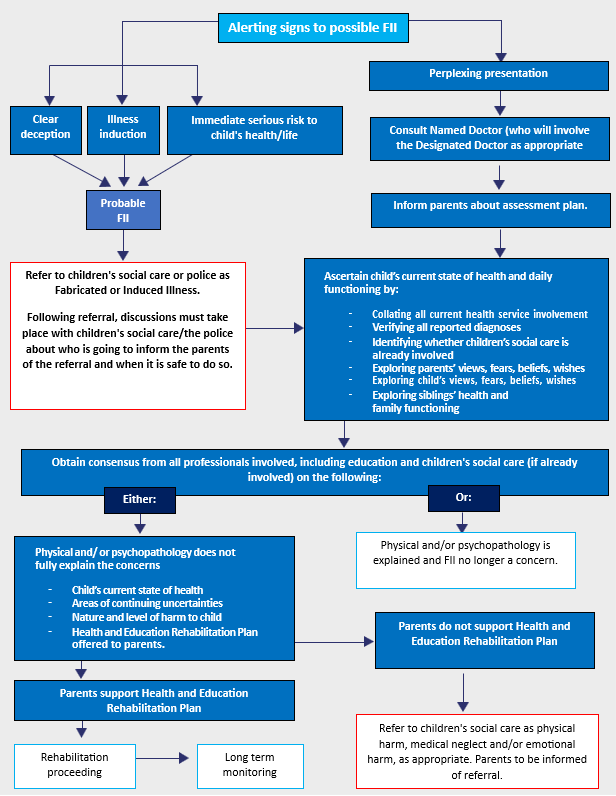

Ultimately, the aim is to assess the impact of PP/FII on the child’s physical and emotional health and development, and to consider how to best safeguard the child’s welfare. This requires a sound and clear multi-agency approach. Early recognition and intervention are recommended to explore the possible causes of a PP. There is a need to establish whether PP are fully explained by a verified condition in the child, or whether there has been some element of exaggeration or fabrication of illness with consequent physical, emotional, social or educational harm to the child. Please refer to the pathway approach (below) to be followed after the identification of alerting signs.

This diagram outlines the pathway approach to be followed after identification of alerting signs. A full copy can be found in Appendix 1

Definition of Key Terms

Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS)

In Medically Unexplained Symptoms (MUS), a child’s symptoms, of which the child complains or parents report, and which are presumed to be genuinely experienced, are not fully explained by any known pathology. The symptoms are likely based on underlying factors in the child (usually of a psychosocial nature), and this is acknowledged by both clinicians and parents. MUS can also be described as ‘functional disorders’ and are abnormal bodily sensations which cause pain and disability by affecting the normal functioning of the body. The health professionals and parents work collaboratively to achieve evidence-based therapeutic work in the best interests of the child or young person. MUS may also include PP or FII.

Perplexing Presentations (PP)

The term Perplexing Presentations (PP) has been introduced to describe the commonly encountered situation when there are alerting signs of possible FII (not yet amounting to likely or actual significant harm), when the actual state of the child’s physical, mental health and neurodevelopment is not yet clear, but there is no perceived risk of immediate serious harm to the child’s physical health or life. The essence of alerting signs is the presence of discrepancies between reports, presentations of the child and independent observations of the child, implausible descriptions and unexplained findings or parental behaviour

Such cases require an active approach by paediatricians and an early collaborative approach with children and families. It is important to recognise any illnesses that may be present, whilst not subjecting children to unnecessary investigations or medical interventions, always bearing in mind the fact that verified illness and fabrication may both be present.

Children and young people with PP often have a degree of underlying illness, and exaggeration of symptoms is difficult to prove and even harder for health professionals to manage and treat appropriately.

Fabricated or Induced Illness (FII)

FII is a clinical situation in which a child is, or is very likely to be, harmed due to the parent(s) behaviour and action. This is carried out to convince doctors that the child’s state of physical and/or mental health and neurodevelopment is impaired (or more impaired than is actually the case). FII results in physical and emotional abuse and neglect, including harm caused inadvertently by the process of treatment. The parent does not necessarily intend to deceive, and their motivations may not be initially evident.

FII is a spectrum of presentations rather than a single entity. At one end of the spectrum, less severe presentations may include a genuine belief that the child is ill, or exaggeration by carers of the child’s existing symptoms. At the other end of the spectrum, the behaviour of carers includes deliberately inducing symptoms in the child.

For the purpose of this Practice Guidance, the presentations can be broadly divided into the following areas, whilst recognising that they are not mutually exclusive:

- Exaggeration of existing symptoms to an extent which leads to potential harm to the child, or significantly impacts their day-to-day life;

- Fabrication of signs or symptoms;

- Falsification of hospital charts and records, and specimens of bodily fluids

- Induction of illness by a variety of means.

- Consideration should also be given to FII presentations of the child with mental health symptoms in addition to presentations of physical symptoms.

According to statutory definitions of abuse and neglect (HM Govt, 2018), FII is referred to under the category of physical abuse. This is because FII often results in a physical impact on children. However, it should be recognised that some parental presentations can also be potentially regarded as neglectful in terms of the child’s needs not being recognised or met, and the emotional impact of these presentations on children cannot be underestimated.

Features of PP and FII Parent/caregiver motivation and behaviour

There are two possible, and very different, motivations underpinning the parent’s need: the parent experiencing a gain and the parent’s erroneous beliefs. In the first, the parent experiences a gain (not necessarily material) from the recognition and treatment of their child as unwell. The parent is thus using the child to fulfil their needs, disregarding the effects on the child. This may include a financial gain for the parents in terms of entitlement to additional benefits based on the fact that the child has a certain condition.

The second motivation is based on the parents’ erroneous beliefs, extreme concern and anxiety about their child’s health (e.g., nutrition, allergies, treatments). This can include a mistaken belief that their child needs additional support at school and an Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP). The parent may be misinterpreting or misconstruing aspects of their child’s presentation and behaviour. In pursuit of an explanation, and increasingly aided by the internet, the parent develops a belief about what is wrong with their child.

However, regardless of the motivation or behaviour of the parent or caregiver, the focus must remain on the impact on the child.

Parents/Carers may exhibit a range of behaviours when they believe that their child is ill. A key task for professionals is to distinguish between the overanxious parent/carer and those who exhibit excessive health-seeking behaviour. In addition, recognising PP/FII can be especially difficult because often the reported signs and symptoms cannot be confirmed as they may only be witnessed by the parent/carer (when they are being exaggerated or imagined) or they may be inconsistent (when they are induced or fabricated).

Alerting signs to possible PP/FII

In the child

- Reported physical, psychological or behavioural symptoms and signs not observed independently in their reported context.

- Unusual results of investigations (e.g., biochemical findings, unusual infective organisms).

- Inexplicably poor response to prescribed treatment.

- Some characteristics of the child’s illness may be physiologically impossible, e.g., persistent negative fluid balance, large blood loss without a drop in haemoglobin.

- Unexplained impairment of the child’s daily life, including school attendance, aids, and social isolation.

Parent behaviour

- Parents’ insistence on continued investigations instead of focusing on symptom alleviation when reported symptoms and signs not explained by any known medical condition in the child or by the results of examinations and investigations.

- Repeated reporting of new symptoms.

- Repeated presentations to and attendance at medical settings, including Emergency Departments.

- Inappropriately seeking multiple medical opinions.

- Providing reports by doctors from abroad which are in conflict with UK medical practice.

- Child repeatedly not brought to some appointments, often due to cancellations by the parent.

- Not able to accept reassurance or recommended management, and insistence on more, clinically unwarranted, investigations, referrals, continuation of, or new treatments (sometimes based on internet searches).

- Objection to communication between professionals.

- Frequent vexatious complaints about the professional.

- Not letting the child be seen on their own.

- Talking for the child/child repeatedly referring or deferring to the parent.

- Repeated or unexplained changes of school (including to home schooling), of GP or of paediatrician/health team.

- Factual discrepancies in statements that the parent makes to professionals or others about their child’s illness.

- Parents pressing for irreversible or drastic treatment options where the clinical need for this is in doubt or based solely on parental reporting.

Harm to the child:

Harm to the child can take several forms. Some of these are caused directly by the parent, intentionally or unintentionally. Harm can also be a result of medical intervention from investigating or treating reported symptoms, and therefore, the harm is caused inadvertently. The following three aspects need to be considered when assessing potential harm to the child. As FII is not a category of maltreatment in itself, these forms of harm may be expressed as emotional abuse, medical or other neglect, or physical abuse. There is also often a confirmed, co-existing physical or mental health condition.

Child’s health and experience of healthcare

- The child undergoes repeated (unnecessary) medical appointments, examinations, investigations, procedures & treatments, which are often experienced by the child as physically and psychologically uncomfortable or distressing

- Genuine illness may be overlooked by doctors due to repeated presentations

- Illness may be induced by the parent (e.g., poisoning, suffocation, withholding food or medication), potentially or actually threatening the child’s health or life.

Effects on child’sdevelopment and daily life

- The child has limited/interrupted school attendance and education

- The child’s normal daily life activities are limited

- The child assumes a sick role (e.g., with the use of unnecessary aids, such as wheelchairs). The child may genuinely believe that they are sick or have a disability.

- The child is socially isolated.

Child’s psychological and health-related well-being

- The child may be confused or very anxious about their state of health

- The child may develop a false self-view of being sick and vulnerable. Adolescents may actively embrace this view and then may become the main driver of erroneous beliefs about their own sickness. Increasingly, young people caught up in sick roles are themselves obtaining information from social media and from their own peer group, which encourages each other to remain ‘ill’

- There may be active collusion with the parents’ illness deception

- The child may be silently trapped in the falsification of illness

- The child may later develop one of a number of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial difficulties.

Response

In cases where there is a risk of significant harm to the child, an urgent referral to Children’s Social Care should be made in line with CYSCP and NYSCP procedures. These include cases where there is –

- Clear deception, such as falsifying documents or interfering with specimens, or unexplained results of investigations suggesting contamination.

- Actual induction of illness, such as suffocation or poisoning.

- Immediate serious risk to the child’s health or life.

Where there are significant immediate concerns about the safety of a child, the police should be contacted via 999

In all other cases, where there is no immediate risk to the child’s health, the response should be managed as Perplexing Presentations (Appendix 1 RCPCH PP/FII Guidance Flow Chart).

Response to Perplexing Presentations (PP)

The RCPCH recognise that cases of perplexing presentations are an increasingly common issue for professionals and require a different approach to ‘true’ FII. When there are alerting signs with no immediate serious risk to the child’s health, the response should be managed as ‘Perplexing Presentations’. Practitioners who have concerns regarding PP should discuss these concerns with Safeguarding Leads within their own organisation and agree on the next steps, which include discussing these concerns with the parents/carers and obtaining a ‘health view’ on the presentation. Cases which remain of concern need to be referred to a Consultant Paediatrician or Consultant Psychiatrist (depending on the presentation) by the child’s GP for an overview and medical assessment. All cases of PP should be led by a Consultant Paediatrician, or Consultant Child Psychiatrist/Consultant Clinical Psychologist (dependent on concerns) with advice from the Named Doctor and Trust Safeguarding Children team.

The term Perplexing Presentations and management approach should be explained to the parents and the child, if the child is at an appropriate developmental stage. Parents will be informed of the assessment process, and that information will be gathered from other caregivers and professionals. This should be done collaboratively with the parents and with consent. If parents refuse to consent to this process, consideration needs to be given as to whether the threshold for significant harm has been met and consent overridden.

Liaison with Primary Care:

The GP is likely to have had a higher level of involvement and knowledge of the child and family than other health professionals. GPs involvement and contribution to the management of PP/ FII concerns is essential to ensure that all key information with regard to the child is shared. GPs will also be aware of parental health issues – including both physical and mental health – and these should be taken into consideration as part of any assessment and information sharing.

It is essential that GPs are kept fully informed and involved in the management of children with perplexing presentations or where there are concerns about FII, so they can support children and their families as appropriate as well as work in partnership with other professionals involved to ensure the best outcomes for children.

If there are concerns about the welfare of a child and FII is a consideration, the child’s needs are paramount, and the GP has a duty to share any relevant and proportionate information that may impact the welfare of a child. This includes sharing relevant information about parents and carers as well as the child. GPs are well placed to recognise early symptoms and signs of PP/FII in a child, and as the primary record keeper of all health records, can play a key role in recognising patterns of worrying behaviour from multiple presentations at different settings. If there are concerns about PP/FII and the child is not known to a Consultant, they should be referred to a Paediatrician, Consultant Child Psychiatrist or Consultant Clinical Psychologist (dependent upon the presenting issues) with expertise in symptoms and signs that are being presented. The GP should make it clear about their concerns re possible PP/ FII in the referral letter and what has been discussed with the parents. Timeliness of the referral will depend on presentation. If there are indicators of immediate harm to a child, the response guidance above, in relation to immediate harm, should be followed.

If concerns arise within General Practice, there should be consultation with the Named GP for Safeguarding Children in the first instance. If the Named GP requires further support, they can contact the Designated Professionals Team. When recording concerns about PP/FII, GPs should ensure that these concerns are recorded within the child’s clinical record but that the entry is not visible on online access, as parental awareness of the concern may escalate the risk to the child.

Role of the Consultant Paediatrician, Consultant Child Psychiatrist or Consultant Clinical Psychologist (see RCPCH Guidance for full details of suggested assessment). The key role of the Consultant is to establish, as quickly as possible, the child’s actual current health state of physical and psychological health and functioning and the family context.

This lead clinician should –

- Collate all current medical/health involvement in the child’s investigations and treatment.

- Consider inpatient admission for assessment and direct observations of the child.

- Explore the child’s views with the child alone (if of an appropriate developmental level and age) to ascertain: – the child’s own view of their symptoms; – the child’s beliefs about the nature of their illness; – worries and anxieties; – mood; – wishes.

- Obtain information about the child’s current functioning, including: school attendance, attainments, emotional and behavioural state, peer relationships, mobility, and any use of aids.

- Obtain history and observations from all caregivers, including mothers and fathers, and others if acting as significant caregivers, including obtaining their views on the child’s health difficulties.

- Explore family functioning, including the effects of the child’s difficulties on the family. Health and well-being of siblings

- Explore sources of support which the parent is receiving and using, including social media and support groups. Ascertain whether there has been, or is currently, involvement of early help services or children’s social care. If so, these professionals need to be involved in discussions about emerging health concerns.

It is important to note that some children’s and adolescents’ views may be influenced by and mirror the caregiver’s views. The fact that the child is dependent on the parent may lead them to feel loyalty to their parents, and they may feel unable to express their own views independently, especially if differing from those of their parents. (The RCPCH have developed resources, with input from children and young people, to aid their communication with health professionals) Download RCPCH ‘Being Me’ resources at:

- https://www.rcpch.ac.uk/resources/being-me-supporting-children-young-people-care

- https://childprotection.rcpch.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2021/03/Perplexing-Presentations-FII-Guidance.pdf

When paediatricians become concerned about a perplexing presentation, an opinion from an experienced colleague needs to be obtained, and a tertiary specialist may be necessary.

Reaching a consensus formulation about the child’s current health, needs, and potential or actual harm to the child

Following the medical and psychosocial assessment, a multi-professional meeting is required to gain a ‘consensus’ about the child’s state of health needs, and whether the PP is explained and resolved by a verified medical condition in the child, or whether concerns remain.

Additionally, agreement should be reached regarding the following:

- Whether further investigations and seeking further medical opinions are warranted in the child’s interests.

- How the child and the family need to be supported to function better alongside any remaining symptoms, using a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan

- If the child does not have a secondary care paediatric Consultant involved in their care, consideration needs to be given to involving local services.

- The health needs of siblings.

It is essential to invite all professionals who are involved with the child and family to the professionals’ meeting, including GP, Consultants, private doctors and other significant professionals who have observations about the child, including education and Children’s Social Care if they have already been involved.

This meeting should be chaired by the Named Doctor (or a clinician experienced in safeguarding with no direct patient involvement) to ensure a degree of objectivity and to preserve the direct doctor-family relationship with the responsible clinician.

The outcome of this meeting may be that FII is suspected, in which case a referral to Children’s Social Care is required. However, it may be that this threshold has not been met, and a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan should be developed to support the child and family. In all cases of perplexing presentation, it is recommended that a further professional meeting be arranged for 3 months, convened by the Named Doctor. This ensures ‘drift’ is avoided and that professionals involved reconvene to review progress.

Following the initial professionals’ meeting, a consultation should be held with the parents, the Consultant Paediatrician and a paediatric colleague to explain the outcome of the assessment to parents and the child, if age appropriate. The ‘consensus opinion’ is offered to the parents with the acknowledgement that this may well differ from what they have previously been told and may diverge from their views and beliefs. Consideration should also be given as to whether a referral to Early Help is required at this stage.

Chronologies

Chronologies of significant health events can be useful in understanding recurring patterns of behaviour and concerns in PP and FII. They are particularly valuable when there is uncertainty about the extent or pattern of past reported illnesses/significant events, and/or there is a requirement to make a case for a significant harm threshold for child protection or court proceedings.

Although very useful, chronologies are usually time-consuming to compile and are not always necessary. They can also be misleading as a standalone or single agency document without a summary and overall analysis. The need to complete a multiagency chronology should be agreed upon by professionals, and there should be a clear time period and completion date. It should also be clear who will be collating, summarising and analysing the combined document.

If the decision is made that chronologies are required, they should –

- Provide a summary of key information pertaining to the child – they should not just replicate the child’s health record

- Pay particular attention to the specific concerns that have been raised about the child

- Clearly state what has been said, by whom and to whom

- Record what has been reported or observed, and whether this was observed by professionals

- Record the source of information, e.g. ‘History taken from Mother’

- Be written in a way that can be understood by colleagues from other non-medical or professional backgrounds.

To ensure chronologies can be combined to create a multiagency document, professionals must use the chronology template provided (Appendix 2)

Health and Education rehabilitation plan

This plan should be developed and implemented, regardless of the status of the children’s social care involvement.

Development of the Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan requires a coordinated multidisciplinary approach and negotiation with parents and children, and usually will involve their attendance as appropriate at the relevant meetings. The Plan is led by one agency (usually health) but will also involve education and possibly children’s social care. It should also be shared with an identified GP. The Plan must specify timescales and intended outcomes. There needs to be agreement about who in the professional network will hold responsibility for coordinating and monitoring the Plan, and who will be the responsible paediatric consultant (most likely to be a secondary care paediatrician).

It is recommended that the child is not discharged from paediatric care, even if there is no current verified illness to explain all the alerting signs, until it is clear that rehabilitation is proceeding. The plan should address issues such as reducing medical interventions, improving the daily functioning of the child and a revised view of the child’s actual state of health.

The question of future harm to the child depends on whether the parents/caregivers are able to recognise any possible harm and change their beliefs and actions in such a way as to reduce or remove the harm to the child, and whether they are engaging with the process and plan. In the eventuality that parents disengage or request a change of paediatrician, consideration should be given to the risk that this presents to the child and reassessment of the risk should be initiated.

See Appendix 3 for an example Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan template.

Review of the plan

The Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan needs to be reviewed regularly with the family according to the timescales for achieving the specified outcomes, especially regarding the child’s daily functioning. This should continue until the aims have been fulfilled, the child has been restored to optimal health and functioning, and the previous alerting signs are no longer of concern.

An agreement needs to be reached by the professionals involved and the family about who will review the plan and when. It is essential to identify a lead professional to coordinate care and organise regular review of the plan.

If the child has either a Child in Need or a Child Protection Pla,n it may be appropriate for a social worker to take the lead in coordination in conjunction with health and education teams, as the aims of the Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan would form part of that plan. An important element of the Health and Education Rehabilitation plan is that the parent must be able to demonstrate a realistic view of the child’s health and health-related needs and to be seen to have communicated this to the child.

All children who have required a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan, unless there is a permanent positive change in primary caregivers, will require long-term follow-up by a professional at the closure of the plan. Education and primary health professionals are the appropriate professionals to monitor the children’s progress and to identify re-emerging or new concerns. Depending on individual circumstances, it is advisable to continue to be alert to possible recurrence of concerns either in the child(ren) or their siblings.

If the parents and child (if of an appropriate developmental level) can understand the need for, and can agree on a Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan, a referral to Children’s Social Care may not be necessary as long as the plan is being monitored carefully, proceeding satisfactorily, and agreed goals are being reached. However, if not already made, a referral to Early Help should also be considered to provide additional support to the child/young person with the plan.

It is important that the situation for the child is resolved and that they can return to a more normal lifestyle.

A safeguarding referral to CSC should be considered if:

- Attempts by the treating team to help, or if contact is broken, so that no information is available.

- If the parents do not support the Health and Education Rehabilitation plan, reject the ‘consensus opinion’, insist on further interventions or further opinions, or if they ‘sack/dismiss’ the Consultant involved and demand a change of Doctor,

- If the child develops new and unexplained physical symptoms or reports non-physical symptoms.

The referral to Children’s Social Care should be discussed with parents, and the reasons for professional concern explained. It is important to emphasise the nature of the harm to the child, including physical harm, emotional harm, medical or other neglect and avoidable impairment of the child’s health or development. If a referral to Children’s Social Care is made for FII, then a multi-agency strategy meeting will be held (see section below re response to referrals and strategy meetings).

Response to Fabricated or Induced Illness

Where there are sufficient concerns that a child may be suffering, or is likely to suffer significant harm resulting from a parent or carer’s persistent attempt to fabricate, induce or exaggerate an illness, a referral should be made to Children’s Social Care as soon as possible in line with North Yorkshire Safeguarding Children Partnership and City of York Safeguarding Children Partnership multi-agency procedures.

At the point of referral to CSC, advice should be sought from the organisational safeguarding lead regarding whether or not parents should be made aware of the referral, since doing so may increase the risk for the child/children. There will be situations where an urgent referral to CSC is required, for example, induction of illness, poisoning or suffocation. If a Professional is concerned about the immediate safety of a child, then an urgent referral must be made, and consideration should be given to calling 999. The referrer should be clear regarding the significance and immediacy of the concerns.

A detailed referral should include:

- A clear explanation of any verified diagnoses with a clear description of the functional implications of the diagnosis (es) for the child.

- Description of independent observations of the child’s actual functioning, medical investigations, detailing all medical services involved and the consensus medical and professional view about the child’s state of health.

- Information given to the parents and child about diagnoses and implications.

- Description of the help offered to the child and the family to improve the child’s functioning (e.g. the Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan).

- The parents’ response.

- Full description of the harm to the child, and possibly to the siblings, in terms of physical and emotional abuse, medical, physical and emotional neglect.

All referrals to CSC must identify the exact nature of the concerns and explicitly state why FII is suspected.

Discussions should also take place between the referrer and CSC about what the parents or carers will be told, by whom and when, and details recorded on the child’s records.

Response by Children’s Social Care & Multi-Agency Strategy Meeting

CSC will decide and record within 1 working day what action is required in response to the referral. Lead responsibility for action taken to safeguard and promote the children’s welfare lies with CSC. The police must be involved throughout the safeguarding investigation. In all cases where it is believed the information indicates suspected FII, there should be an assessment undertaken, which may result in a multi-agency strategy meeting which considers all children within the family. The strategy must be a ‘face-to-face’/virtual meeting, and the appropriate professionals must attend. However, non-attendance of one or two key professionals should not delay the meeting if it is indicated that the child may be at risk of significant harm. Any professionals who are unable to attend the meeting should send a summary of their involvement and whether they have any concerns re FII. Key professionals will include:

- Team manager or practice supervisor CSC

- Named/Designated Doctor

- Specialist/Named Nurse Safeguarding from the relevant organisation

- Lead Paediatric Consultant/CAMHS Consultant (as applicable)

- Detective Sergeant from the North Yorkshire Police Vulnerability Assessment Team (VAT)

- The referrer

- Other allied health professionals involved in the child’s care

- Other Consultants involved in the child’s care.

- Adult Mental Health Consultant (if involved with a parent’s care)

- General Practitioner

- School or early years setting representative

- Legal advisor to local authority

During the strategy meeting, specific consideration must be given to what information is to be shared with the parents and when. In addition, decisions about involving the child in discussions must also take place, and consideration must be given to any relevant therapeutic work. The Paediatric Consultant or relevant senior clinician, for example CAMHS Consultant, is the lead health professional pertaining to the child’s health care. All agencies must work together in making and taking forward decisions about the future action, recognising individual roles.

The RCPCH recommends that any interventions from CSC will include supporting the Health and Education Rehabilitation Plan. In addition, the child will need to be protected from being taken to other health professionals unnecessarily by the parent if they continue to give unreliable information about the child.

If the referral is declined as not reaching the threshold for Children’s Social Care involvement and there is professional disagreement regarding the presenting concerns and/or the agreed management plan, multi-agency escalation processes should be followed. The Designated Professional’s for Safeguarding Children should be consulted, in line with LSCP conflict resolution or challenge procedures. The Designated Professional’s team also provide a valuable source of expert advice and support to health care professionals and colleagues from partner agencies. They can offer safeguarding supervision or facilitate professional discussions, particularly where the presenting issues are very complex

Information Sharing, Consent and Confidentiality

The child’s best interests must be the overriding consideration in making decisions about sharing information. In cases of suspected or confirmed PP/FII, all decisions about what and when to tell parents and children should be made by senior staff within the multi-agency team. While professionals should seek, in general, to discuss any concerns with the family and, where possible, seek their agreement to action, this should only be done where such discussion and agreement-seeking will not place a child at increased risk of significant harm. In all cases where the police are involved, the decision about when to inform the parents (about referrals from third parties) will have a bearing on the conduct of the police investigation.

It is important when obtaining and sharing information that consideration is given to what information is shared – this should be relevant and proportionate to the concern. For example, only relevant health and social information about parents should be shared in order to protect the children. Further advice can be obtained from your organisation’s Safeguarding Lead, and it may be necessary to consult with your organisation’s legal advisor. Any decision on whether or not to share information must be clearly documented. Where there are sufficient concerns that a child may be suffering or is likely to suffer significant harm resulting from a parent or carer’s persistent attempt to fabricate, induce or exaggerate an illness, a referral should be made to CSC as soon as possible in line with LSCP multi-agency procedures.

Record Keeping

Records should use clear and straightforward language, should be concise and accurate, not only in fact, but in differentiating between opinion, judgements and hypotheses. It should be clearly recorded what is reported by the parents/carers and what has been directly observed by the practitioners. Where it is considered that illness may be fabricated or induced, the records relating to the child’s symptoms, illness, diagnosis and treatments should always include the name (and agency) or the person who gave or reported the information. This should be dated and signed legibly.

Police response

During the process of information sharing and assessment, it may become apparent that there are indicators that a crime has been committed. This should be taken into consideration during all stages of assessment and interventions, and the police will provide direction regarding professional intervention in order to avoid disrupting any possible criminal investigation/process.

Emergency action

Circumstances of the child can change at any point during the investigation; for example, if parents or carers become aware of concerns, they may escalate the abuse. Decisions about the need for immediate action to safeguard the child/ren should be kept under constant review and appropriate legal advice sought where required.

References

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (2013) Fabricated or Induced Illness by Carers. Practical guide for Paediatricians (2009) Update statement.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) Perplexing Presentations/Fabricated or Induced illness in Children. RCPCH guidance (2021)

UK Government. 1989. Children Act. 1989. Available at:

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/41/contents

Working Together to Safeguard Children – a guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children (2023)

Glaser, D. & Davis, P. (2019) ‘For debate: Forty years of fabricated or induced illness (FII): where next for paediatricians? Paper 2: Management of perplexing presentations including FII’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 104, pp.7-11

Safeguarding Children in Whom Illness is Fabricated or Induced – Department for Health (2008)

Multi-agency procedures

North Yorkshire: http://www.safeguardingchildren.co.uk

City of York: http://www.saferchildrenyork.org.uk/

Appendices

Page reviewed: February 2026

View all our news

View all our news